“According to the EIA weekly inventory figures, US production has fallen by nearly 1 mm b/d or 7% in only five weeks – the second-sharpest decline in US production ever outside of hurricane-related activity.”

While oil storage, or the lack thereof, continues to make headlines, we are more interested in what will happen once inventories reach maximum capacity. While it may sound counterintuitive, if global oil inventories became completely full, the market would immediately become balanced. Without anywhere to store surplus crude, the entire global petroleum supply chain would be forced into a “just-in-time” dynamic with supply equaling demand overnight. Producers would have to undertake widespread shut-ins of existing wells, and these actions would have material impacts for years to come.

Once demand starts to recover, it will be impossible to restart production fast enough to keep inventories from drawing down sharply. In our past letters, we have discussed many of the problems embedded in the global oil supply base from the shales to aging non-OPEC fields outside of the US. Each of these issues will immediately come to the fore once demand recovers and supply is unable to arrest its embedded decline. There is a strong likelihood that oil prices experience an extremely violent move higher sometime in the next eighteen months if not even sooner.

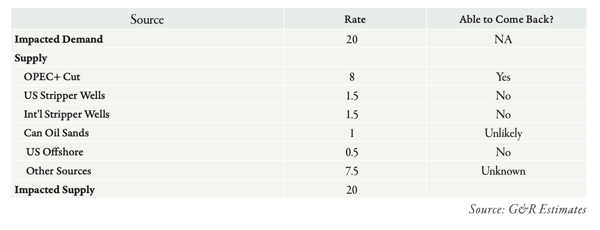

To understand why, consider the following. Global quarantining likely reduced total oil demand by 25% in April, or 25 mm b/d. While this likely marked the low point in oil demand, May should still see impairments of approximately 20 mm b/d compared to normal, equating to global oil consumption of 80 mm b/d. We estimate April production averaged 101 mm b/d, implying the market will be oversupplied by 21 mm b/d in May.

Once storage is full at some point in mid-May, a good portion of this 21 mm b/d will have to be shut in.

The recent production cuts announced by OPEC+ on April 9th are not nearly enough. While the “headline number” calls for cuts of 9.7 mm b/d, we believe the true magnitude is closer to 8 mm b/d from April’s levels. Approximately 1.5 mm b/d will be shut in from so-called “stripper wells” in the United States. These wells are extremely old and nearing the end of their productive lives. In most cases they produce less than 5 b/d each yet make up nearly 20% of total US production in aggregate. Since their production rates are so low and their water production is high, the stripper wells incur operating costs in excess of the oil price and have started being shut in already. While it is more challenging to get data on international stripper wells, we estimate another 1.5 mm b/d will be shut in from this group as well. Canadian oil sands production is both expensive to produce and yields a heavier grade crude that often trades at a discount to WTI. We estimate that at least 1 mm of oil sands and related production will come offline imminently. On April 22, 2020, The Wall Street Journal reported that offshore Gulf of Mexico production is being abandoned as we speak. In total, we would not be surprised if at least 500,000 b/d came offline from offshore sources.

Even accounting for all these sources, there is still nearly 5 mm b/d of production that will need to be shut in once storage is full. To put the enormity of this figure in perspective, at their fastest rate of growth ever, the shales grew by 2 mm b/d over the course of a year, compared with 5 mm b/d of global production that must be curtailed in a matter of weeks. This is already starting to happen according to the most real-time data available. According to the EIA weekly inventory figures, US production has fallen by nearly 1 mm b/d or 7% in only five weeks – the second-sharpest decline in US production ever outside of hurricane-related activity.

Most of these “involuntary” cuts will never come back online. In some cases, shutting in a well for a prolonged period will irreparably damage the wellbore or reservoir. The stripper wells meanwhile were only marginally economic to begin with on an operating basis and would never justify the capital cost to drill through the cement plugs used to cap them. While offshore production is accustomed to shutting in production for short periods during hurricanes, longer-term curtailment requires the well to be permanently sealed making re-entry nearly impossible. As Tim Duncan, CEO of offshore producer Talos Energy, told The Wall Street Journal on April 22nd, 2020: “In offshore, we don’t shut in fields, we shutter them.” The only source of curtailed oil that can likely come back online is the OPEC+ cuts of 8 mm b/d. While these cuts represent a large volume, they will not be nearly enough once global demand begins to normalize.

In our latest in-depth commentary, Oil Supply is About to Collapse, we explore this subject and many others. If you are interested in reading the research document, download the full commentary here.