The article below is an excerpt from our Q3 2023 commentary.

In late 2021, we made a bold and deeply contrarian call: we predicted massive capital flows into renewable energy could potentially become history’s worst malinvestment ever. Our call looks correct three years later and the consequences have emerged with a vengeance.

Over the past six months, several notable wind and solar projects have been canceled, delayed, or impaired due to rising costs. Stocks that were once market favorites have now pulled back hugely. Wind turbine manufacturer Orstead is off 73% from its peak and 47% this year alone. Renewable provider Nextera is off 50% from its peak and 30% this year. Hydrogen maven Plug Power is off an incredible 95% from its peak and 68% this year. The Invesco Solar ETF is off 58% from its peak and 35% this year.

In recent months, Orstead has taken a $4 bn write-off on its offshore US wind projects, canceled its Norwegian projects, and fired its CEO. In November, Siemens withdrew its wind turbine manufacturing plant in Portsmouth, Virginia. A September UK offshore wind concession auction failed to attract a single bid. Renewable proponents, who claim costs are lower than conventional energy sources, argued the relatively high 44 GBP tariff was insufficient to encourage wind development.

TWO MASSIVE WIND FARM PROJECTS OFF THE COAST OF NEW JERSEY HAVE BEEN CANCELED. TWO PARTIALLY COMPLETED WIND FARM PROJECTS OFF THE COAST OF RHODE ISLAND AND MASSACHUSETTS ARE NOW ON HOLD AS THE DEVELOPERS WRESTLE WITH REGULATORS ON TARIFF STRUCTURES, NOW MADE OBSOLETE BECAUSE OF RAPIDLY RISING CONSTRUCTION AND INSTALLATION COSTS.

Two massive wind farm projects off the coast of New Jersey have been canceled. Two partially completed wind farm projects off the coast of Rhode Island and Massachusetts are now on hold as the developers wrestle with regulators on tariff structures, now made obsolete because of rapidly rising construction and installation costs.

As The Wall Street Journal published on November 12th, “The Path to Green Energy is Getting Messier.”

In 2016, we asked ourselves an important question: what role should renewable energy play going forward? If one studies the history of energy, its production and consumption, new technologies with superior energy efficiency always displace old technologies with inferior energy efficiency. As the pundits argued, if wind and solar were ideal forms of energy with superior energy efficiencies, we would be forced to leave behind our oil and gas investments and embrace renewables, as renewables would ultimately displace all hydrocarbon-related energy production.

As energy investors, it was imperative for us to develop a framework to judge renewables and their actual cost structures.

We have read excellent works by Professors Charles Hall and Vaclav Smil on energy efficiency or energetics. Professor Hall developed the energy return on investment concept, or EROI, which measures how much input energy is required to generate a unit of usable power output – the key energetic measure of efficiency. Professor Smil, a prolific author, writes captivatingly about the history of energy advancement. We ultimately developed our lens through which to judge renewable energy. We also noted that a new energy technology had never replaced an incumbent without having superior energetics. We were amazed that so few analysts or policymakers had questioned the energetics, or EROI, of wind and solar and sought the answers ourselves.

Despite being heralded as the future, wind and solar have terrible EROIs. Compared with coal or natural gas, sunlight and wind are not energy-dense. Compare the energy from a gas stove with a stiff breeze or a sunny afternoon; they are different orders of magnitude. Since renewable energy density is so low, their size must be enormous to generate the same output. A modern windmill stands 80 stories tall with rotor blades that are 600 feet in diameter. A 100 MW solar installation, enough to power 20,000 households, requires a staggering 139 million square feet of PV solar panels. Large size means copious raw materials, which consume enormous energy. As a result, the energy required to generate output is very high, and the EROI is low. A combined cycle natural gas plant enjoys an EROI of 30:1, compared with the best wind and solar at 10:1 and 5:1, respectively. Unfortunately, wind and solar are intermittent and must be “buffered” by either building redundant capacity or through grid-scale battery backup, reducing their overall EROI further to as low as 3-5:1. Based upon our framework, wind and solar could never replace conventional energy given their inferior EROI.

We recorded countless podcasts, including a 45-minute-long video entitled “History of Energy.” At the fall 2022 Grant’s Interest Rate conference, we also extensively presented why renewables would never be successful. Our presentation was entitled: “The Great Renewable Disaster: Inside the European Petrie Dish.” Readers who are also Grant’s Interest Rate subscribers, we recommend you listen to our presentation.

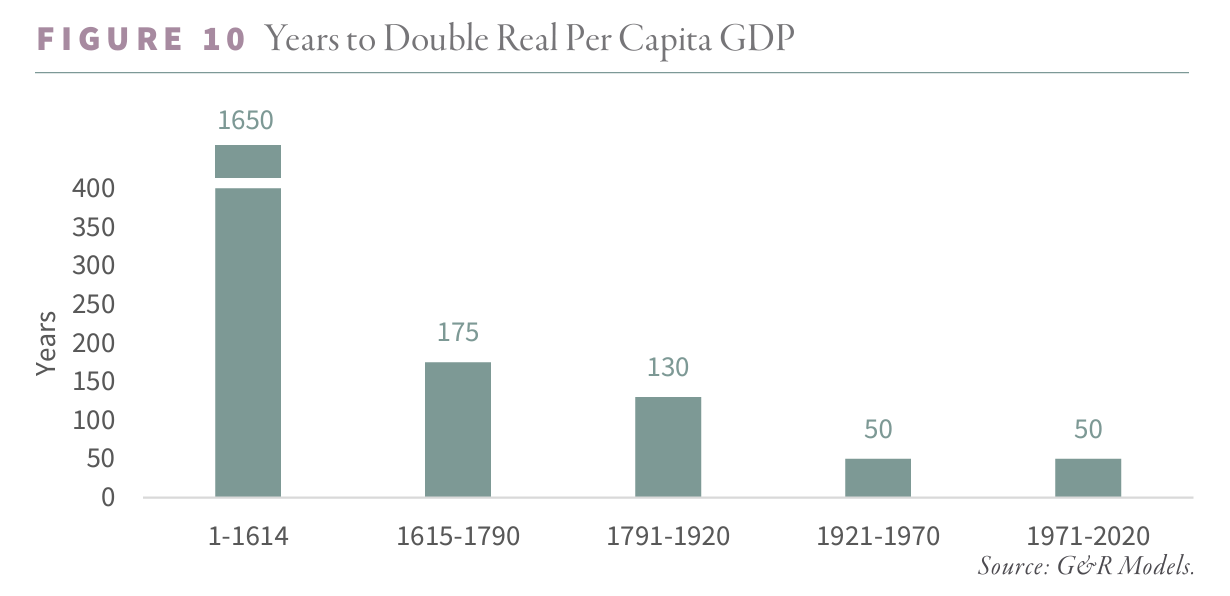

Our views were controversial. For most of history, society relied upon biofuels for energy: crops for food and fodder and wood for heat and construction materials. We estimated that such an energy economy had an EROI of 5:1. Given the low energy efficiency, economic growth was nearly impossible. We estimate it took sixteen centuries to double real per capita GDP, equating to an increase of 0.04% annually. The slow growth made sense when looking through the lens of energy. We estimate that energy consumption averaged 17 GJ per person yearly for most of human history. Given an EROI of 5:1, 3.5 GJ was spent generating energy. Food consumed 4 GJ per person annually, while other necessities, such as animal fodder and shelter, consumed 10 GJ per person. There was no surplus energy available, and with no surplus energy, economic growth proved impossible.

As London grew in the seventeenth century, it ran out of easily accessible wood and was forced to burn coal for heat. The improved energy efficiency was immediately apparent, and Britain’s EROI jumped to 10:1. The energy needed to make energy dropped, allowing for material surplus energy for the first time in human history. Surplus energy allowed for economic growth; almost overnight, activity accelerated. After having taken sixteen centuries to double, real per capita GDP doubled again in 175 years, then 130 years, then 50 years, then 50 years again.

Coal gave way to oil and natural gas, each with ever-improving EROI. The result is today’s modern world, in which developed economies consume 175 GJ of energy per capita annually – a ten-fold increase compared with the historical norm. Surplus energy, meanwhile, went from nil to nearly 150 GJ per capita annually – a seventy-fold improvement over the last 375 years.

Transitioning to wind and solar, with EROIs closer to biofuels than fossil fuels, would mean immediately lowering surplus energy by nearly 40% and returning to an energetic system incapable of delivering any real growth. We concluded this was not feasible.

While we focused on renewables’ poor energetic efficiency, analysts were fixated on their falling costs. According to Bloomberg, solar costs have fallen 80% since 2010, from $40 to $7, while wind costs have fallen 40%, from $9 to $5 per MWh. The industry claimed that Moore’s Law had crept into renewable energy. They claimed prices would continue to fall and eventually compete with conventional energy within a matter of years.

It seemed strange that costs could compete with natural gas combined cycle turbines if the underlying energy efficiency were so poor: undoubtedly, the better the EROI, the lower the cost. We built a model to help explain the dramatic fall of renewable expenses and found our answer.

The last decade was notable for meager energy costs and extremely low-interest rates. The rise of shale production, beginning in the early 2010s, pushed most energy prices lower by nearly 90%. Interest rates, meanwhile, reached the lowest level in history, with $17 trillion of debt sporting negative nominal interest rates by 2019. Renewable energy is hugely energy and capital-intensive. Therefore, it is no surprise that costs fell drastically throughout the 2010s.

We concluded that between 50 and 70% of the fall in wind and solar energy’s LCOE was attributable directly to lower capital and energy costs. We wrote:

If our models are correct and energy prices and capital costs rise going forward, the impact on renewable energy will be dramatic. We calculate that solar costs could increase from 7 cents to 20 cents per kWh while wind costs could rise from 4.5 cents to 6.0 cents per kWh. Nearly a decade of cost savings would be wiped out in both cases.

Instead of falling to meet conventional energy requirements, we predicted renewable costs would rise – an incredibly contrarian view at the time. This is precisely what is happening today. While many articles cite rising interest rates and materials (a function of higher energy), they treat these cost pressures as temporary. We disagree. A decade of abundant energy and loose liquidity helped mask renewables’ poor efficiency. That is now over.

In their latest, highly cited Levelized Cost of Energy report, the investment bank Lazard acknowledges the rising cost of renewables. According to their numbers, solar’s average LCOE rose nearly 60% between 2021 and 2023, wiping out eight years of improvement. The high end of their solar range surged by an incredible 135% over the same period. For wind, the average cost rose 32%, with the high-end of the range advancing 50%, again wiping out eight years of improvement. Despite the unexpected cost increase, the pundits continue to get it wrong. In their recent report, Lazard sensitizes various forms of energy across a 25% fuel price adjustment; however, the analysis seems to capture only direct fuel usage. Gas, nuclear, and coal all increase, but solar and wind costs remain fixed. This is simply incorrect. As we have seen over the last two years, renewable costs are disproportionally impacted when energy prices rise due to their relatively inferior energy efficiency. Although they do not directly consume fuel, renewable energy consumes considerable “embedded” energy in all the steel, cement, and copper required.

OVER THE PAST NINE YEARS, THE IEA ESTIMATES $3.5 TRILLION WAS INVESTED IN WIND AND SOLAR GENERATION, ALL OF WHICH WE BELIEVE SHOULD BE CATEGORIZED AS MALINVESTMENT. THIS SPENDING GENERATED LESS THAN 3,500 TWH, A MERE 12% OF TOTAL ELECTRICITY GENERATION. IN 2022 ALONE, NEARLY $600 BN WAS SPENT TO ADD 500 TWH. THE CAPITAL INTENSITY OF LAST YEAR’S INSTALLATION WAS ALMOST 20% GREATER THAN THE AVERAGE OVER THE PREVIOUS NINE YEARS. SO MUCH FOR MOORE’S LAW.

Over the past nine years, the IEA estimates $3.5 trillion was invested in wind and solar generation, all of which we believe should be categorized as malinvestment. This spending generated less than 3,500 TWh, a mere 12% of total electricity generation. In 2022 alone, nearly $600 bn was spent to add 500 TWh. The capital intensity of last year’s installation was almost 20% greater than the average over the previous nine years. So much for Moore’s Law.

With deficits soaring and energy becoming more scarce and expensive, how much longer can we continue down the renewable path?

Intrigued? We invite you to download or revisit our entire Q3 2023 research letter, available below.

Registration with the SEC should not be construed as an endorsement or an indicator of investment skill, acumen or experience. Investments in securities are not insured, protected or guaranteed and may result in loss of income and/or principal. Historical performance is not indicative of any specific investment or future results. Investment process, strategies, philosophies, portfolio composition and allocations, security selection criteria and other parameters are current as of the date indicated and are subject to change without prior notice. This communication is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services. Nothing in this communication is intended to be or should be construed as individualized investment advice. All content is of a general nature and solely for educational, informational and illustrative purposes. This communication may include opinions and forward-looking statements. All statements other than statements of historical fact are opinions and/or forward-looking statements (including words such as “believe,” “estimate,” “anticipate,” “may,” “will,” “should,” and “expect”). Although we believe that the beliefs and expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable, we can give no assurance that such beliefs and expectations will prove to be correct. Various factors could cause actual results or performance to differ materially from those discussed in such forward-looking statements. All expressions of opinion are subject to change. You are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements. Any dated information is published as of its date only. Dated and forward-looking statements speak only as of the date on which they are made. We undertake no obligation to update publicly or revise any dated or forward-looking statements. Any references to outside data, opinions or content are listed for informational purposes only and have not been independently verified for accuracy by the Adviser. Third-party views, opinions or forecasts do not necessarily reflect those of the Adviser or its employees. Unless stated otherwise, any mention of specific securities or investments is for illustrative purposes only. Adviser’s clients may or may not hold the securities discussed in their portfolios. Adviser makes no representations that any of the securities discussed have been or will be profitable. Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio.